Definition

An orphan is defined as a child under the age of 18 years whose mother, father, or both biological parents have died (including those whose vital status is reported as unknown, but excluding those whose vital status is unspecified). For the purpose of this indicator, we define orphans in three mutually exclusive categories:

- A maternal orphan is a child whose mother has died but whose father is alive;

- A paternal orphan is a child whose father has died but whose mother is alive;

- A double orphan is a child whose mother and father have both died.

The total number of orphans is the sum of maternal, paternal and double orphans.This definition differs from that sometimes used by United Nations and other agencies, where the definitions of maternal and paternal orphans each include children who are double orphans.

Data

Source

Statistics South Africa (2003 – 2025) General Household Survey 2002 – 2024. Pretoria, Cape Town: Statistics South Africa.

Analysis by Katharine Hall & Sumaiyah Hendricks, Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town.

Analysis by Katharine Hall & Sumaiyah Hendricks, Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town.

Notes

- Children are defined as persons aged 0 – 17 years.

- Population numbers have been rounded off to the nearest thousand.

- Sample surveys are always subject to error, and the proportions simply reflect the mid-point of a possible range. The confidence intervals (CIs) indicate the reliability of the estimate at the 95% level. This means that, if independent samples were repeatedly taken from the same population, we would expect the proportion to lie between upper and lower bounds of the CI 95% of the time. The wider the CI, the more uncertain the proportion. Where CIs overlap for different sub-populations or time periods we cannot be sure that there is a real difference in the proportion, even if the mid-point proportions differ. CIs are represented in the bar graphs by vertical lines at the top of each bar.

What do the numbers tell us?

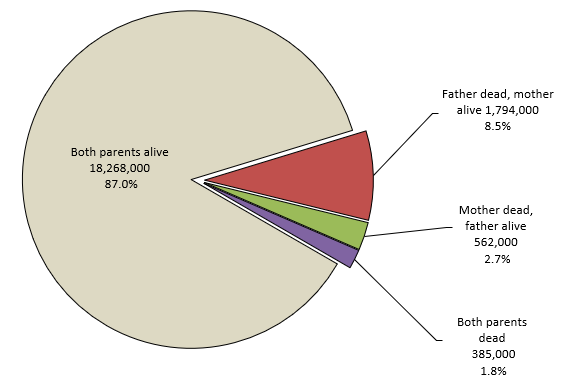

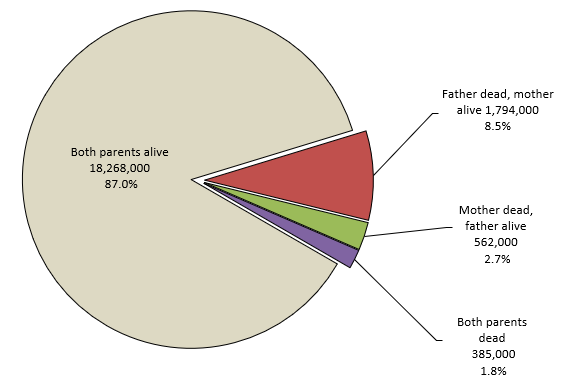

In 2024, there were 2.7 million orphaned children in South Africa. This includes children without a living biological mother, or father or both parents, and is equivalent to 13% of all children in South Africa. The majority (65%) of all orphans in South Africa are paternal orphans (with deceased fathers and living mothers).

The total number of orphans increased by over a million between 2002 and 2009, after which the trend was reversed. By 2017, orphan numbers had fallen to below 2002 levels. This was largely the result of improved access to antiretrovirals. Contrary to expectations, the number of orphaned children did not increase significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, and in 2022 the orphaning rates in all categories (maternal, paternal and double orphans) were lower than they were in 2019. This may be because COVID-19 related deaths were most prevalent among older people, while prime-age adults with children were less vulnerable.

Source: Statistics South Africa (2025) General Household Survey 2024. Pretoria: Stats SA.

Analysis by Katharine Hall and Sumaiyah Hendricks, Children’s Institute, UCT.

Orphan status is not necessarily an indicator of the quality of care that children receive. It is important to disaggregate the total orphan figures because the death of one parent may have different implications for children than the death of both parents. In particular, it seems that children who are maternally orphaned are at risk of poorer outcomes than paternal orphans – for example, in relation to education.[1]

In 2024, 3% of all children in South Africa were maternal orphans with living fathers, 9% were paternal orphans with living mothers, and a further 2% were recorded as double orphans. In total, 5% of children in South Africa (950,000 children) did not have a living biological mother and 10% (2.2 million) did not have a living biological father. The numbers of paternal orphans are high because of the relatively high mortality rates among men in South Africa, as well as a greater probability that the vital status, and perhaps even the identity, of a child’s father is unknown. Around 290,000 children have fathers whose vital status is reported to be “unknown”, compared with fewer than 30,000 children whose mothers’ status is unknown.

The number and share of children who are double orphans, more than doubled between 2002 and 2009, from 361,000 to 886,000 after which the rates fell again. In 2018, there were 471,000 children who had lost both their parents, but the numbers rose again to over 580,000 in 2019. Subsequently, the number of double orphans dropped back to around 540,000 in 2021, dropped below 500,000 in 2022 and dropped further to below 400,000,000 in 2024.

There is some variation across provinces. The Eastern Cape, for example, has historically reported relatively high rates of orphaning, reflecting a situation where rural households of origin carry a large burden of care for orphaned children. In terms of provincial shares, double orphans are concentrated mostly in three provinces: KwaZulu-Natal (accounts for 22% of double orphans), Gauteng (20%) and the Eastern Cape (13%). Together these three provinces are home to nearly 60% of all double orphans.

KwaZulu-Natal has the second largest child population and the highest orphan numbers, with 635,000 children (15% of children in that province) recorded as orphans who have lost a mother, a father or both parents. In the North West, 18% of children are reported to be orphaned, and 16% of children are orphaned in the Free State. The Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga and Northern Cape have the same orphaning rates (14%) but because their child populations are smaller, they have lower numbers of orphaned children. From 2020, Gauteng emerged as the province with the second highest orphaning numbers. In 2024, more than 520,000 children in Gauteng were single or double orphans. A rise in orphan numbers within the province does not necessarily mean that there has been an increase in parental deaths; it could equally mean that children who are orphaned in Gauteng are now more likely to remain there, rather than being sent to another province. In other words, provincial orphaning rates are a reflection both of parental deaths and of the dynamics of extended families, including migration, family ties across provinces, and childcare arrangements. The lowest orphaning rates are in the Western Cape, where 9% of children are maternal, paternal or double orphans.

The poorest households carry the greatest burden of care for orphaned children. Just over 40% of all double orphans are resident in the poorest 20% of households.

The likelihood of orphaning increases as a child gets older. Across all age groups, the main form of orphaning is paternal orphaning (deceased father), which increases from 4% among children under six years of age, to 13% among children aged 12 – 17 years. While less than 1% of children under six years are maternal orphans, the maternal orphaning rate increases to 5% in children aged 12 – 17 years.

The total number of orphans increased by over a million between 2002 and 2009, after which the trend was reversed. By 2017, orphan numbers had fallen to below 2002 levels. This was largely the result of improved access to antiretrovirals. Contrary to expectations, the number of orphaned children did not increase significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, and in 2022 the orphaning rates in all categories (maternal, paternal and double orphans) were lower than they were in 2019. This may be because COVID-19 related deaths were most prevalent among older people, while prime-age adults with children were less vulnerable.

Source: Statistics South Africa (2025) General Household Survey 2024. Pretoria: Stats SA.

Analysis by Katharine Hall and Sumaiyah Hendricks, Children’s Institute, UCT.

Orphan status is not necessarily an indicator of the quality of care that children receive. It is important to disaggregate the total orphan figures because the death of one parent may have different implications for children than the death of both parents. In particular, it seems that children who are maternally orphaned are at risk of poorer outcomes than paternal orphans – for example, in relation to education.[1]

In 2024, 3% of all children in South Africa were maternal orphans with living fathers, 9% were paternal orphans with living mothers, and a further 2% were recorded as double orphans. In total, 5% of children in South Africa (950,000 children) did not have a living biological mother and 10% (2.2 million) did not have a living biological father. The numbers of paternal orphans are high because of the relatively high mortality rates among men in South Africa, as well as a greater probability that the vital status, and perhaps even the identity, of a child’s father is unknown. Around 290,000 children have fathers whose vital status is reported to be “unknown”, compared with fewer than 30,000 children whose mothers’ status is unknown.

The number and share of children who are double orphans, more than doubled between 2002 and 2009, from 361,000 to 886,000 after which the rates fell again. In 2018, there were 471,000 children who had lost both their parents, but the numbers rose again to over 580,000 in 2019. Subsequently, the number of double orphans dropped back to around 540,000 in 2021, dropped below 500,000 in 2022 and dropped further to below 400,000,000 in 2024.

There is some variation across provinces. The Eastern Cape, for example, has historically reported relatively high rates of orphaning, reflecting a situation where rural households of origin carry a large burden of care for orphaned children. In terms of provincial shares, double orphans are concentrated mostly in three provinces: KwaZulu-Natal (accounts for 22% of double orphans), Gauteng (20%) and the Eastern Cape (13%). Together these three provinces are home to nearly 60% of all double orphans.

KwaZulu-Natal has the second largest child population and the highest orphan numbers, with 635,000 children (15% of children in that province) recorded as orphans who have lost a mother, a father or both parents. In the North West, 18% of children are reported to be orphaned, and 16% of children are orphaned in the Free State. The Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga and Northern Cape have the same orphaning rates (14%) but because their child populations are smaller, they have lower numbers of orphaned children. From 2020, Gauteng emerged as the province with the second highest orphaning numbers. In 2024, more than 520,000 children in Gauteng were single or double orphans. A rise in orphan numbers within the province does not necessarily mean that there has been an increase in parental deaths; it could equally mean that children who are orphaned in Gauteng are now more likely to remain there, rather than being sent to another province. In other words, provincial orphaning rates are a reflection both of parental deaths and of the dynamics of extended families, including migration, family ties across provinces, and childcare arrangements. The lowest orphaning rates are in the Western Cape, where 9% of children are maternal, paternal or double orphans.

The poorest households carry the greatest burden of care for orphaned children. Just over 40% of all double orphans are resident in the poorest 20% of households.

The likelihood of orphaning increases as a child gets older. Across all age groups, the main form of orphaning is paternal orphaning (deceased father), which increases from 4% among children under six years of age, to 13% among children aged 12 – 17 years. While less than 1% of children under six years are maternal orphans, the maternal orphaning rate increases to 5% in children aged 12 – 17 years.

Technical notes

Children are defined as orphaned if their parent is known to be deceased or if the vital status of the parent is unknown. Orphans are identified in three mutually exclusive categories: maternal orphans, paternal orphans and double orphans. The three categories add up to the total number of orphans.

The definition used here differs from that commonly used by the UN agencies where the definitions of maternal and paternal orphan include children who are double orphans: for instance, all children who have lost a mother (whether or not their father is alive) are included in their measure of maternal orphans. Using those definitions, there is double counting and maternal, paternal and double orphan numbers add up to more than the total number of orphans.

The definition used here differs from that commonly used by the UN agencies where the definitions of maternal and paternal orphan include children who are double orphans: for instance, all children who have lost a mother (whether or not their father is alive) are included in their measure of maternal orphans. Using those definitions, there is double counting and maternal, paternal and double orphan numbers add up to more than the total number of orphans.

The SAECR 2024 tracks trends on the status of children under 6.

The SAECR 2024 tracks trends on the status of children under 6.